Chapter 26: The Four Sons

Faithful Obedience

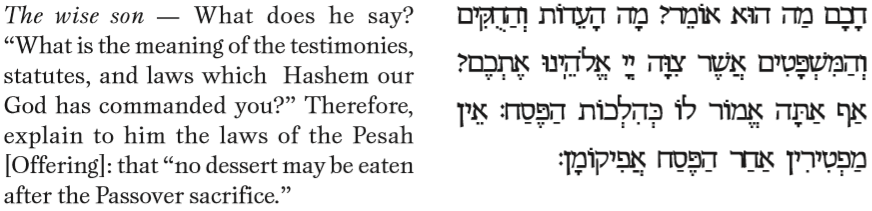

חכם מה הוה אומר

The wise son — What does he say?

The Haggadah cites the questions of the four sons, the first two being the wise son and the wicked son. Whereas the wise son is to be offered an elaborate explanation of the laws of Pesah, the wicked son, we are told, is to be “smacked” for asking, “What is this service to you?” Wherein lies the difference between the questions posed by these two sons? The difference between the wise son and the wicked son, is, quite simply, the difference between one who serves his Creator faithfully and one who does not. Despite the fact that we must observe the mitzvot regardless of our understanding of their underlying principles or lack thereof, we are still permitted and encouraged to identify, as much as possible, the reasons behind the mitzvot. Nevertheless, one should preferably research the reasons behind the mitzvot only after his actual performance. Otherwise, he may develop a disrespectful attitude towards the mitzvah in question, if he does not find, with his limited intellect, a satisfactory rationale. Thus, prior to receiving the Torah, Bnei Yisrael declared, “Na’aseh venishma” (“We will do and we will hear”), implying that they will first perform the mitzvot, and only thereafter will they inquire as to their underlying rationale. Herein lies the difference between the wise son and the wicked son. Regarding the wise son, the Torah writes, “When your son will ask you Tomorrow...” This son does not present his line of questioning now, at the time of the Pesah-offering. He obeys and observes, attributing his doubts and lack of comprehension to his own intellectual limitations. He follows the principles established by the Talmud Yerushalmi (in “Perek Helek”), “If it [the Torah] seems empty – it is from you.” (See also the comments of the Bet Yosef, Yoreh Dei’ah 181.) Only “tomorrow,” after the Pesah observance, does the wise son present his queries regarding the essence of this mitzvah, longing to properly understand all the underlying concepts relevant to the mitzvah of the Pesah-offering. The wicked son, by contrast, asks, “What is this service to you?” He questions the rationale behind the mitzvah right there and then, at the time of the offering itself. He insists on fully comprehending the philosophical underpinnings of the mitzvah prior to its observance. This way, should the explanation not be to his intellectual liking, he will then discard the mitzvah as meaningless and fail to perform. He will refuse to believe that God’s infinite wisdom knows the reasoning behind the mitzvot. Therefore, the Haggadah bids us to “blunt his teeth,” to criticize him for his lack of belief. (Haggadah Hazon Ovadiah

The Heresy of the Wicked Son

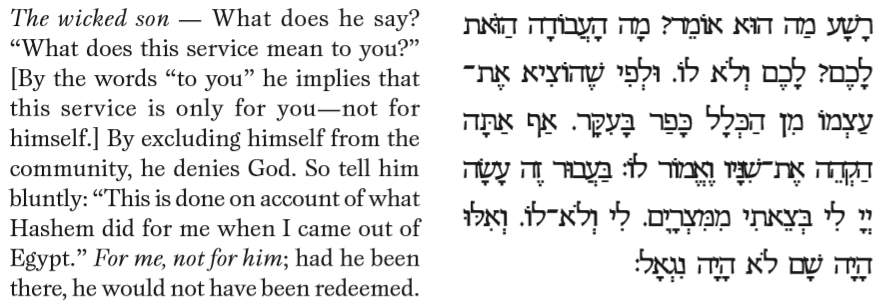

רשע מה הוה אומר

The wicked son — What does he say?

The Haggadah cites the question of the wicked son: “What is this service to you?” The “Bet HaLevi” (in his work on the Torah, Parashat Bo) notes that the wicked son did not question the need to serve the Almighty. Rather, he denies the fact that the Korban Pesah ritual constitutes service of God: “...this service...” He fails to recognize the religious quality latent in the Pesah ceremony. He claims that one needs to devise new means of serving Hashem, means which are more in keeping with the tendencies of one’s time and location. This is similar to many elements within contemporary Jewish society, who insist we replace the laws of the Torah with new rituals which they themselves develop. Indeed, the parashah in which this pasuk is found deals with an educated son, familiar with the events of Yetziat Mitzrayim, and the miracles which occurred. However, he has adopted the heretical stance calling for the elimination of certain mitzvot. Having suggested a possible reason behind a certain mitzvah, he claims that since the alleged “reason” no longer applies, the mitzvah itself is no longer in force, Heaven forbid. Unfortunately, many people associate mitzvot with given time-periods, thus concluding that in today’s situation they no longer apply. This fundamental error is rooted in lack of Torah knowledge. The vast sea of information within the corpus of Torah contains many reasons behind the mitzvot, some more obvious and others far more subtle. The prophet remarks in the name of Hashem, “Just as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are My ways beyond yours, and My thoughts beyond yours” (Yeshayahu 55). One who lacks Torah knowledge cannot appreciate its vastness, and, consequently, he arrives at the heretical conclusion of the wicked son of the Haggadah. (Shirat Yehudah) Rav Tzvi Hirsh Levine zt”l of Berlin was once approached by David Friedlander, a leading reformer in his day, who asked him about several mitzvot which, he thought, were no longer applicable. “I am sure,” said the reformer, “that were Moshe Rabbeinu alive today, he would have written a Torah in consonance with the spirit of the day.” Rav Levine answered with a story of a merchant who hired a driver to bring him to the market. They made an agreement, in accordance with halachah, that should the merchant not arrive to his destination on time, the driver would not only forfeit his payment, but he would also have to compensate the merchant for the lost profit. Just as they embarked on their journey, however, torrential rain came pouring down from the sky. Before long, the rain turned into sleet, and eventually into snow. The heavy blizzard covered the roads, and the travelers were lost. Although they miraculously arrived at their destination, it was too late – the fair had already ended. The driver demanded his salary, and the merchant demanded recompense for the lost sales. The two brought their case before the local Rabbi, who ruled in favor of the merchant, ordering the wagon-driver to pay his customer in full for all that he lost for having missed the fair. Infuriated, the driver turned to the Rabbi and asked, “Rabbi, how could you force me to pay? This circumstance was beyond my control! Do you consider one who transgressed a violation unintentionally the same as you would look upon an intentional violator?” In an effort to calm the nerves of the embittered driver, the Rabbi answered, “I am not requiring that you pay. It is the Torah that obligates you, based on the legally binding agreement that you made with the merchant. You should have no complaints against me!” The driver thought for a second and replied, “Tell me something, Rabbi. When was the Torah given – on what date?” “Of course, Shavuot, the day of the giving of the Torah, is the sixth of Sivan!” The driver cried, “Right, the sixth of Sivan! Sivan is during the summertime, when the roads are clear! No storm could block my path, no snow could obstruct my journey. In Sivan, I would have had a clear road, I would not have been even a minute late! No, Rabbi. You cannot decide a case in the winter based on the Torah which was given in the summer. Were Moshe to have written the Torah in the winter, I would have unquestionably won this case, for the law would be different based upon the time of year!” Thus, Rav Levine pointed out that David Friedlander may be compared to that driver. The rabbi concluded his remarks, and David Friedlander left the room humiliated. (Haggadah Hazon Ovadiah)